How to Slay Princesses & Game Writing

Don’t forget, the fate of the world rests on your shoulders

In my game writing workshops (new cohort starting December 2025!) and in other articles, I often talk about a notion of a ‘core experience’

This can be seen as akin to the ‘fantasy’ of who your character is as a player, and what you’re doing in both the gameplay and the story. Crucially, this is not necessarily the same thing as the character’s precise end goal, nor is it necessarily the same as the plot. For instance, when my students identify the core experience by a character’s name, it’s a misunderstanding. We aren’t ‘Geralt of Rivia’ in The Witcher’s core experience, because ‘being a Geralt’ isn’t a type of person in a primal, raw, psychological sense. Rather, we and Geralt, combined, embody a kind of person.

From the following article:

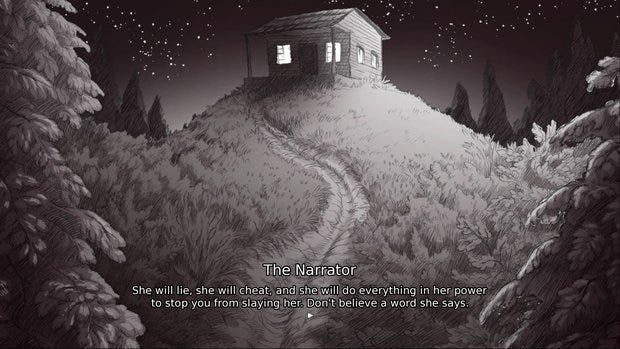

Slay the Princess (2023) begins with a perfect version of this — something where we don’t just get ‘scene-setting’, we get ‘role-setting’ and ‘goal-setting’ —>

You’re on a path in the woods, and at the end of that path is a cabin. And in the basement of that cabin is a Princess.

You’re here to slay her. If you don’t, it will be the end of the world.

Perfect!

We understand completely what we’re doing and why.

There are many reasons why this is good, many of which overlap in turn.

We only like confusion if confusion is motivated, if we trust the storyteller putting us in that position, if we understand enough that it’s challenging without being too much effort. We -rarely- like a high level of confusion at the very start of a story, or at the very least, we want something to hold onto alongside it.

Why do we care about roles? Well, a -role- is easier to grasp and get into in any story than a -name-. I can feel far more about a ‘mother’ and ‘son’ than I do about ‘Kate’ and ‘Brian’; I can grasp a ‘manager’ and ‘employee’; and so on. The more the two roles -contrast- in some kind of relationship to each other, the easier this is to differentiate. So in another story, describing two ‘friends’ would give us a role, sure, but it gives us less than another way of describing such characters — a ‘depressed friend’ and a ‘bragging friend’ immediately differentiate because they introduce a kind of vocational variation in -type- of friend. So here, with you being a slayer of princesses and implied world-saver, we have the implied nature of the princess as someone who may attempt to manipulate and destroy set against us.

With this stuff about roles, the contrast is kind of like potential energy — like how if you compress a spring, you know that letting go will cause a release as it extends out. The situations themselves contain potential drama.

We know where we are - the word ‘princess’ and cabin and the references to saving the world all imply that we’re in a fantastical medieval type setting, which also acts as a kind of ‘instruction’ as to how to act. This genre code is non-explicit — it’s entirely possible we aren’t in a medieval time period — but in the absence of anything non-medieval, our mind leaps to these reasonable assumptions.

The points above can be true of many types of storytelling — but if we’re playing a videogame, it’s likely we’re wanting an especially experiential focus, we want to inhabit a -role-. In my earlier article, I brought up Geralt, but no-one cares about being ‘Geralt’ until they understand being that kind of monster-hunter in a world of human monsters. Being Geralt becomes the ultimate prize as his personality becomes clearer and we’re invested. Of course we want to be -him-, but the role always precedes the personality, both then reinforcing the other in a virtuous cycle when done well.

If you get nothing else from this piece today, understand this: the player needs to know what they are, more than who they are. Clarity and strength in this will have exponential benefits for everything that follows, even if you play around with it as the game develops.

Now, if you’ve played Slay the Princess, you’ll know how funny all of this is: the game utterly screws with our clarity about almost everything over time, even and especially who -we- are and who the -princess- is. It does this in ways that directly respond to whatever choices we are making, inferring the assumptions we’ve been acting under and then seeming to needle us and cajole us in relation to those assumptions. For example — if we act like the princess is not going to be bad and that we might romance her somehow, and persist in that assumption? It’s not precisely true to say we’re wrong. But this — and any other interpretation — is a narrative trap prepared for us, one that, were we to replay the game, might cause us to violently pursue other options in response to the game’s previous playing of us as players.

However!

All of that playfulness only works as well as it does because of this utterly clear setup.

You may have heard of the five Ws - Who, What, Where, When, Why - most often applied in high school to non-fiction writing about real events.

This stuff is not just important for -good writing- though — for philosophers, it’s a matter of moral urgency.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle — friend of this Substack — wrote in his Politics that the following were greatly important not just in describing but evaluating the morality of actions and events:

(1) the Who, (2) the What, (3) around what place (Where) or (4) in which time something happens (When), and sometimes (5) with what, such as an instrument (With), (6) for the sake of what (Why), such as saving a life, and (7) the (How), such as gently or violently…And it seems that the most important circumstances are those just listed, including the Why.

As an example:

How could we advise the Athenians whether they should go to war or not, if we did not know their strength (How much), whether it was naval or military or both (What kind), and how great it is (How many), what their revenues amount to (With), Who their friends and enemies are (Who), what wars, too they have waged (What), and with what success; and so on.

Ignorance does not mean making a bad action, so much as not entirely being as responsible morally for the action at all:

Thus, with ignorance as a possibility concerning all these things, that is, the circumstances of the act, the one who acts in ignorance of any of them seems to act involuntarily, and especially regarding the most important ones. And it seems that the most important circumstances are those just listed, including the Why.

We do not need to agree with Aristotle that such ‘clarity’ is even possible — not that it’s even that simple in philosophy, for varying levels of accuracy and subjectivity call into question ‘truth’ in many circumstances, especially one like this. So if it becomes an ideal to aim for in real life decision making, we’re going to need a way of dealing with the imperfect nature of the -actual- data we’re likely to encounter in the course of our decisions.

So when we are thinking about video game writing — a form where we call upon the player to decide upon actions, often with moral consequences — the five ‘w’s can be considered more than just a matter of clear writing. The core experience isn’t just about focusing your writing and gameplay to help players inhabit their character’s role better: what we do here has big consequences for the choices players make and how they feel about those consequences. The clarity of the five ‘w’s in stuff like Slay the Princess appeals innately to our sense of whether we’re actually informed about the actions and choices we are making. They feel good in this sense — ‘great, I know what to do!’ — and as games so often give -direct objectives- in their UI text, they feel like they can give a more objective standard of truth than real life does.

Which means — luring us into a false sense of security, perhaps.

Now, Slay the Princess states its ‘w’s explicitly only to then pull apart our surety about them during the game — but we don’t all need to so explicitly state this stuff. (It’s great here and a valid aesthetic choice, it’s just not the only way of doing things). As with any structural principle, using them as a thought experiment and a lens — i.e. “What will my player feel/think about WWWWW at X point in the game, and why? How could I manipulate things for that to land differently, or to play off those likely expectations?” Narrative feedback and ‘narrative QA’ are especially helpful here — even to the point of A-B testing different versions of different portions, or asking people who play the game to pause and give feedback/guesses/thoughts at particular junctures on various points.

Because, of course, we do not need to give a completely objective accurate framing of all those ‘w’s, because our job is not to enable easy moral choices. Our job is to entertain — and to entertain, as with a twist in a film or a joke or a magic trick, deceiving and revealing deception often leads to delight, especially if it’s done in a fair way that never explicitly lies, but trades off the assumptions we naturally make in the absence of other information.

But whether we state them or not, we the creators -should- know this stuff by the time we’re asking players to play it. And it’s so easy to resist these questions or be afraid of them because we’re not always clear on this during the creative process, and they can of course change. The version of you that plans and edits your material does not have to be the precise same version of you that -writes- it — so allowing yourself to suspend these kinds of concepts, to revisit them, to draw and colour outside of the lines and reshape afterwards — all, of course, valid and useful!

But —

How can you ask a player to play a character and make choices, if you’re unable — even to yourself — to clearly articulate who, what, where, when, why? And if doing so sounds weak or unappealing — do you need a better, stronger sense of the experience, and what will this do, if applied back to the writing to ‘sell’ that all the stronger?

You’re on a path in the woods, and at the end of that path is a cabin. And in the basement of that cabin is a Princess.

You’re here to slay your writing and make your player feel something. If you don’t, it will be the end of your imaginary world.

Don’t forget to subscribe to avoid missing out on these and other articles on game writing, philosophy, culture, and life.

In my day job I write bestselling novels and work as a writer/narrative designer for games including NO MAN’S SKY, METRO:EXODUS, AMERICAN ELECTION, DARK SOULS: THE EYES OF DEATH, and — as I was able to share recently — MAGIC: THE GATHERING.

And - I run game writing classes, including a new cohort of my 13 week+ live MFA-style workshop starting in mid-December 2025 - so apply soon if interested. We aim to create new game projects, pushing our skills to the limit whether we’re writers aspiring or established. More information on the site and on request, including video testimonials from past students.