How to write in video game script format

"What does a video game script even look like?", "Should I use Final Draft?", "What do you mean, there's no such thing as 'a' video game script format?', and more... (Updated 2025)

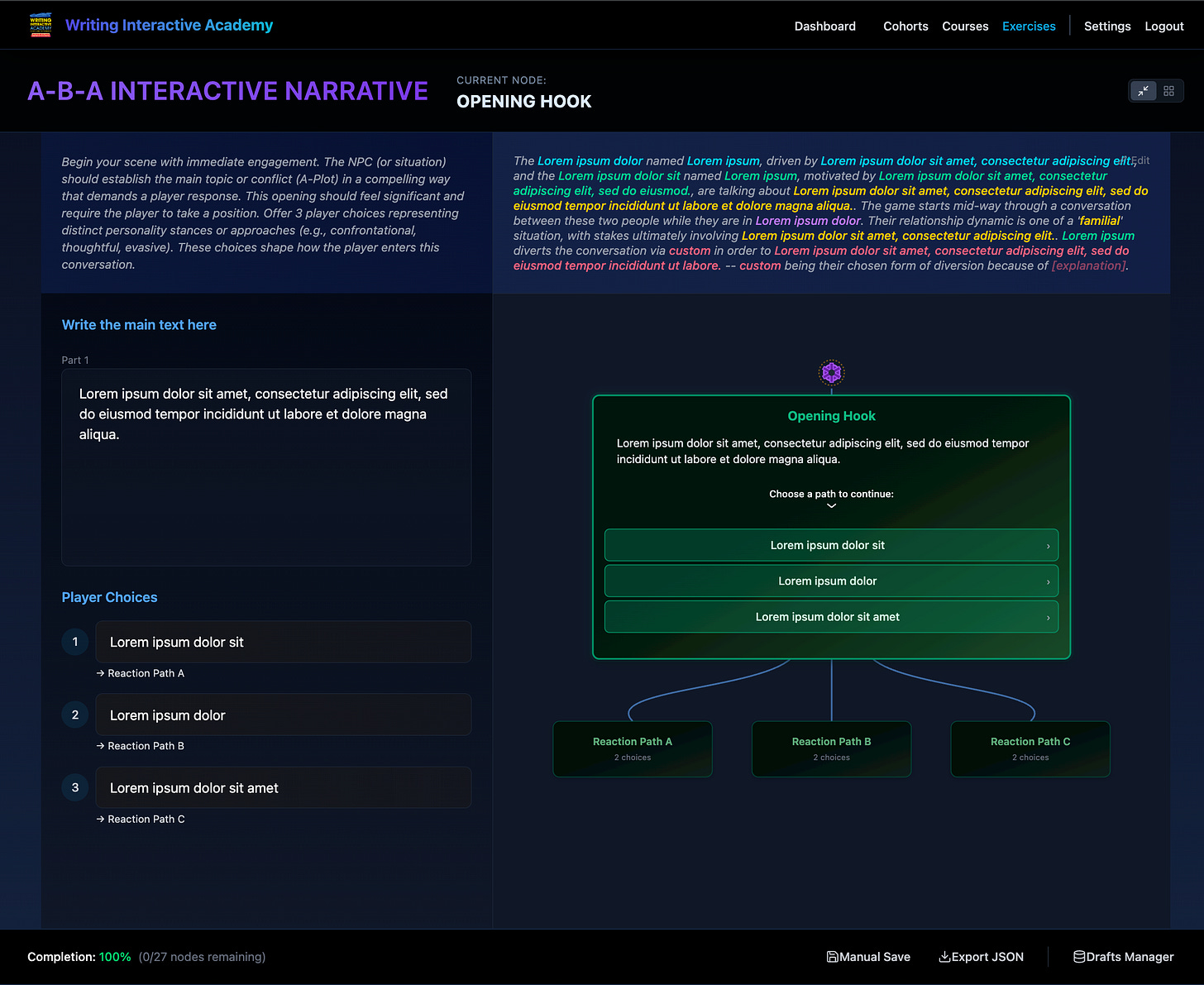

There are many tools out there for writing games. In my workshops we predominantly use Twine, Ink, and for the 101 Branching Dialogue Class, a tool of my own devising for custom narrative structures—>

But for all the time people spend finding the perfect tools, nothing beats actually just writing and making something. In the below, I’ll talk you through …