press 'yes, and' - how improv theory can help your game writing

from Michael Scott's imaginary guns and Superman to Disco Elysium and the Doom Guy punching a story in the face

In comedic UCB-style improv, you're taught to establish a base reality with your scene partner: who are you both, where are you, and what are you doing? This establishment is important to do with words and actions because you have no scenery or props. Consequently, in the first few lines, performers will often say things that reference their relationships and surroundings, such as: "Babe, I can't believe you took me to the zoo!", "It's freezing out here --> Well Eric, I said it was a weird place for a honeymoon", or "So, we're going to jail, son…"

The purpose of this is to give both the audience and the players on stage enough of a sense of who, what, where, and why to process the story and start a narrative.

The audience, however, usually does have some context, which helps, as much improv is spawned by the audience calling out a word, a monologue being read by a performer, or a prompt. Thus, while we don't need to know everything to have some guesses as to what the performers are doing -- this context is still in our minds -- to imagine the audience will automatically 'get it' and connect everything is to misunderstand how active audiences want to be. Likewise, the potential for misunderstanding between the two performers on stage -- who have not pre-planned a scene and are already in its fictional diegesis, acting as fictional people -- is huge. It therefore pays to be clear.

In the above, the performers and audience know the prompt is about two kids playing and that one of them is going to do a ‘lore dump’ — but the performers still take the time to reiterate the context naturalistically, giving each other names and defining their dynamic and personalities. We come to know that they're not just 'two kids', but that one of them is already sounding subtly more precocious ("so happy you could come by") versus the other ("I'm so excited to hang out finally"). The demeanour, body language, and tone of voice of both performers establish the dynamic. Without it being said in actual words, we understand, for instance, that the main girl is going to get super upset if her friend breaks the rules. Information is given to us through wording, acting, body language, and situation, allowing us to understand the dynamic, make guesses, and become invested in the proceedings.

In UCB-style improv, after establishing this 'base reality', part of the performers' 'job' is to 'find the game of the scene'. This involves identifying the unusual thing in what they are doing and how they are acting, seeing what patterns emerge, and -- once a pattern starts being established -- heightening, extending, and playing with it for comedic purposes. So, in the example of the 'lore dump', the 'game' might be found not in the lore dump itself, but in the way the lore dumper behaves and freaks out at any contravention of the lore. This behaviour then becomes funnier and funnier whenever it reoccurs.

The following clip, for instance, shows Michael Scott from The Office failing to ever create a base reality in his own improv classes until the very end. Hilariously, in the sketch itself, the unusual pattern is that Michael can't ever create a base reality -- all he can do is pull out an imaginary gun:

Now, improv and writing have always had an interesting relationship; indeed, it's a format used by many writers to develop sketch comedy throughout the years. However, the way in which the form talks so much about 'games' and 'players' is particularly fascinating when we consider that other medium seemingly just across the street: the videogame interactive narrative. Here, there is literally a player, and we are literally playing a game. Yet, this is often in a sense that's far more controlled and prescribed than improv, as the player rarely has free choice to create, but rather chooses a path through the narrative from among the many paths the writers have shaped for them.

So, if we think about 'base reality' and 'game of the scene', what's useful for game writers? In today's article, I'm going to focus more explicitly on 'base reality', though I will return to 'the game of the scene' in the future, as both concepts are really required in overlap to fully understand the next point.

Something I discuss frequently in my game writing classes is a concept I call the 'Core Experience'. This can be seen as akin to the 'fantasy' of who your character is as a player, and what you're doing in both the gameplay and the story. Crucially, this is not necessarily the same thing as the character's precise end goal, nor is it necessarily the same as the plot. For instance, when my students identify the core experience by a character's name, it's a misunderstanding. We aren't 'Geralt of Rivia' in The Witcher's core experience, because 'being a Geralt' isn't a type of person in a primal, raw, psychological sense. Rather, we and Geralt, combined, embody a kind of person.

Trailers -- especially teaser trailers -- can be incredibly useful for understanding this core experience in many stories. While they can often be misleading, the best teasers are frequently built on the premise of communicating this precise experiential factor.

This is one of my favourite game trailers:

We don't need to know anything about the exact circumstances of this war, this world, where these men are riding towards, what this woman did exactly, or the truth of it all. All we need to know is that he's a monster hunter (we see the monster head, references to the transaction, and a literal mention of 'hunt'). Judging by his friend's reaction to his hesitation, these individuals are not expected to get involved in other people's affairs, and they aren't law enforcers. Intriguingly, however, there is also a sense that our character is prone to such meddling. The narration over the scene makes the moral stakes of the experience incredibly clear: a refusal to choose between lesser evils. And the final lines provide an amazing close: "What are you doing?" the awful torturer cries. "Killing monsters…" We are a monster hunter, of both the supernatural and the human variety, in a world where most choose shades of grey. Boom. That's it.

The following set of teasers for Superman related works are great for setting up different core experience expectations, even though they're ostensibly the same character:

(The first, incidentally, is a goddamn tragedy -- perhaps the greatest difference in 'how good a teaser trailer is' versus the actual film in history.)

The problem is that while the trailer gives a strong sense of mood and power -- suggesting a story of origin and developing humanity/emotion -- the actual film never even approaches the same emotional level as, for example, the Witcher 3 teaser. It's a comic book movie in an okay way, but not a movie that lives up to this almost messianic promise.

Part of this, too, is that the familiarity of the John Williams score, the use of the old Marlon Brando narration, and the evocation of the core origin beats are designed to play on nostalgia. This nostalgia is always hard to live up to, yet it holds huge archetypal potential as a kind of rarefied version of the original story.

It's not a teaser trailer, but the first page of All-Star Superman by Grant Morrison was praised for embodying a similar kind of archetype. It's great in its economy of panels and words, and it sets up a base reality for how this 'take' on Superman is going to proceed: we're not getting some metafictional, grim, and gritty takedown; instead, we're returning to our roots.

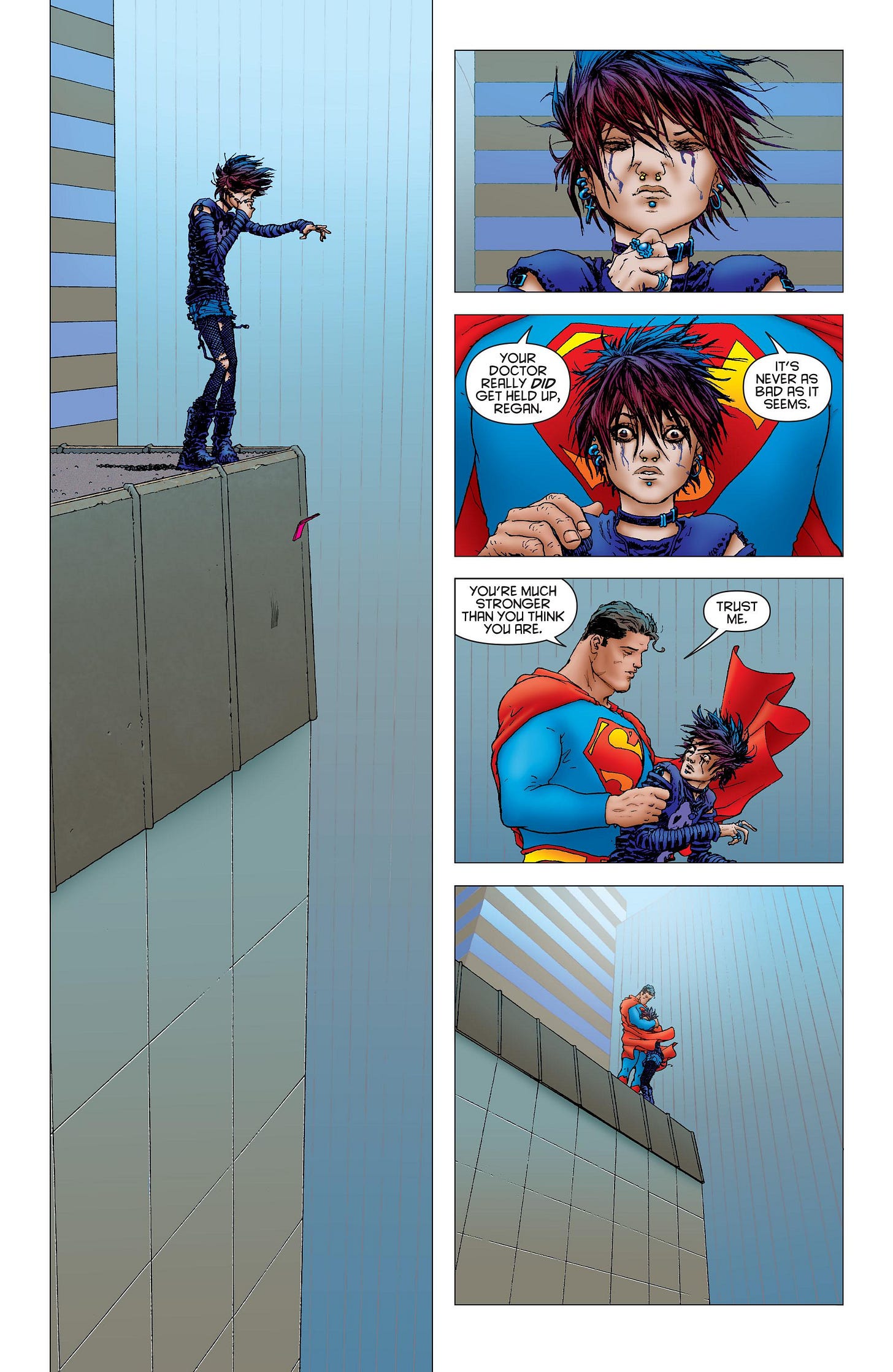

Of course, in longer works, we often see these new groundings of relationships/dynamics occur multiple times over with new pairings as the story develops. The best page in the entire work comes with this, when throughout an issue we see a therapist struggling to reach someone on a phone in the background as Superman flies through a city, until we see a girl on a building's edge:

Again, a mixture of dialogue naming things clearly, a tone of delivery, body language, and positioning -- all of this makes the dynamic and 'point' of the story incredibly clear, without someone needing to explicitly state "Superman is kind". They show us, but in a way where it's not subtext; it's simply clear.

In the most recent Superman teasers for James Gunn's reboot, many internet folk became incredibly upset by the first promotional image, claiming it was somehow anticlimactic, or that the suit did not seem to be figure-hugging:

But what does this image tell us? It suggests we're going to get a Superman who is capable of feeling bad and feeling hurt; a Superman who wears his suit as if it were clothes, implying a surprising level of groundedness compared to many other superhero films (even if this portrayal is still larger than life and Superman remains an incredibly powerful force). Furthermore, it shows us something akin to the sentiment "You're stronger than you think you are", but directed at Superman himself. He is getting back out there, even if it hurts him.

Then, in the teaser trailer for this film, we start with him evidently hurt, accompanied by his dog, themes of love, and all kinds of things that show him experiencing a tough and emotional time, highlighting the difficulty of what he does in this world. Yet, the earlier messianic notes of Superman Returns are not entirely absent. In fact, we see the hope of such 'prayers' actualised in real, embedded situations that seem plausible, allowing us to quickly start joining the dots as to how this man might feel in an incredibly short amount of time.

My final pre-game example is from Game of Thrones. People often forget that the story, in both the TV show and the book, begins not with the Starks, but with the Night's Watch exploring north of the Wall and encountering actual evidence of the supernatural White Walkers, whom we would not see again for a long time. Many might have considered this scene almost irrelevant, and one could imagine more than a few editors attempting to remove it. But why was it so important in setting up the larger work?

It was important because: A) it establishes the exact dynamics we're going to face -- massive social inequality in a medieval society where anyone can die, even the first characters we encounter; B) the 'anyone can die' feel, combined with the supernatural threat, signals that we are now potentially in a horror universe, not just a fantasy one; C) it introduces a ticking clock in the form of a long-term threat on its way; and D) -- most importantly -- without this scene, we would get no supernatural evidence until the dragons at the end of the first book/season (who could arguably be dismissed as de facto animals), and then not again until Season 2's 'shadow baby' scene.

With few exceptions -- which mostly work because they're comedic or because we're intentionally 'spoiled' by marketing and framing in advance (such as From Dusk Till Dawn's shift from crime drama to vampire film halfway through) -- audiences rarely accept a massive genre shift, especially from a realistic to a supernatural world, unless it's heavily foreshadowed or set up in some way. Considering how groundedly bleak and nihilistic Game of Thrones often seems, and the fact that many found the 'shadow baby' scene ineffective on screen anyway, the story as a whole has to be particularly careful about managing our expectations. It's not that the supernatural version of the story is inherently inferior or superior; rather, the reason we're watching what we're watching is heavily linked to our sense of experience.

If you realise this, it helps solve many things in your own head. For example, consider Walter White in Breaking Bad: he is a monster, and in real life, most would not condone his actions or meth production. Yet, Skylar White often comes across as an almost automatic villain when she opposes his drug production, in a way that Hank (Walter's brother-in-law) does not. While misogyny undoubtedly plays a part in many such responses, and arguably creates or amplifies it in some who might already be prone to such views, the underlying narrative logic is this: the "game of the scene" of Breaking Bad -- the thing any parody would immediately hone in on -- is Walter White being 'Frasier-Craney' about meth production, doing hardcore, surprisingly violent things with chemistry while Jesse acts dumb or freaks out at him. This dynamic is what we, the audience, want to see continue. If Walter White stops making drugs, there's no story, and the element we've been enjoying vanishes. Therefore, Hank is not perceived as the enemy because, although he's trying to oppose the drug dealer, he's part of the game -- he's the cop chasing the bad guy. But Skylar, as Walter's wife? She represents the real-life voice saying this is crazy and needs to stop. She is, in effect, anti- the very reason we are even watching. It makes sense for the character who cares most about a protagonist to voice such concerns -- and because shows often make their protagonists male, these 'anti-game' characters frequently end up being wives or girlfriends, hence Skylar.

SO.

Now for some tidy, tangible examples from actual game opening texts, illustrating various approaches to establishing the core experience -- not just stating who we are and where we are in a literal sense, but also establishing tone and hyping us for the kind of experience we are about to play:

SLAY THE PRINCESS

“You're on a path in the woods. And at the end of that path is a cabin. And in the basement of that cabin is a princess. You're here to slay her. If you don't, it will be the end of the world.”

The SLAY THE PRINCESS example makes the nature of the impending dynamic very clear. However, as you'll soon find upon playing it, almost every single element of this initial base reality will become an open story point up for grabs (are we really in the woods? is that really a cabin? is she really a princess? do we have to kill her? why are we killing her? will the world really end? who are we? who is even narrating this?). But, for this ambiguity to be intriguing and destabilising rather than merely confusing, we first need to understand the nature of the situation we're bouncing off. The game is extremely efficient in communicating this initial setup.

STARDEW VALLEY

You are working in an office, and you have a letter you are told to open at this time:

“There will come a day where you feel crushed by the burden of modern life amd your bright spirit will fade before a growing emptiness.”

When you look at the letter:

"If you’re reading this, you must be in dire need of a change.

The same thing happened to me, long ago. I’d lost sight of what mattered most in life… real connections with other people and nature.

So I dropped everything and moved to the place I truly belong.

I’ve enclosed the deed to that place… my pride and joy. It’s located in Stardew Valley, on the southern coast.

It’s the perfect place to start your new life.

This was my most precious gift of all, and now it’s yours.

I know you’ll honor the family name.

Good luck.

Love, Grandpa.”

In STARDEW VALLEY, the approach is less direct in its very first lines, yet it is crystal clear in its evocation of an emotional backstory. This backstory provides an impetus for the player's real-life transition from 'real-life concerns' to the pastoral, welcoming, and kind space of the video game, mirrored through the character's own reading of the letter. We see a grim office environment, and then this letter from a grandfather communicates a moment when one might desire a shift to a new life -- and boom, we shift to that new life.

The ghosts of the old life are referenced within the game (for instance, we see the same corporation we worked for now appearing as a megamart in the town where we're farming). Regardless of how much we invest in the narrative reality of the game, the situational reality it presents resonates deeply with the majority of players. The game has effectively incorporated an almost 1:1 match for 'escapism' as a motivation for this kind of gameplay, framed as a character philosophising to another about this very situation.

And in the letter itself, what key information do we receive? We learn about the farm, who gave it to us, and our relationship with that person.

STANLEY PARABLE

“This is the story of a man named Stanley. Stanley worked for a company in a big building where he was employee number 427. Employee Number 427's job was simple: he sat at his desk in room 427, and he pushed buttons on a keyboard. Orders came to him through a monitor on his desk, telling him what buttons to push, how long to push them, and in what order. This is what Employee 427 did every day of every month and every year, and although others might have considered it soul-rending, Stanley relished every moment that the orders came in, as though he had been made exactly for this job. And Stanley was happy.

And then one day, something very peculiar happened. Something that would forever change Stanley. Something he would never quite forget. He had been at his desk for nearly an hour when he realized that not one single order had arrived on the monitor for him to follow. No-one had showed up to give him instructions, call a meeting, or even say Hi. Never in all his years at the company had this happened - this complete isolation. Something was very clearly wrong. Shocked, frozen solid, Stanley found himself unable to move for the longest time. But as he came to his wits and regained his senses, he got up from his desk and stepped out of his office."

The core experience of The Stanley Parable is essentially: "Explore an office environment and see what the narrator says about your actions." The fantasy isn't so much that you are a particular worker, but, strangely, it's akin to Stardew Valley's use of a similar conceit: we're leaving drudgery for fun. Here, however, instead of escapism into a lovely pastoral farmworld, we're entering a crazytown, absurdist reimagining of what an office and a video game narrative might be in a meta-sense. The opening narrative, therefore, helps guide us towards this frame of mind by establishing A) the status quo, and B) the change. We were doing ordinary life (akin to playing linear games); now we are doing weird life (akin to playing a game without instructions). This narrator leads us into this new state… but, much as in SLAY THE PRINCESS, this narrator is going to hang around.

BIOSHOCK

At the start of Bioshock, we see a POV of someone on a plane, right before it crashes, with the voice over —>

‘They told me, "Son, you're special, you were born to do great things." You know what? They were right.’

Not all 'openings' are confined to a single line. Although our other examples here are primarily 'opening cutscenes', there is nothing stopping us from considering gameplay itself as a form of that same opening. In Bioshock, for instance, the initial spoken line is followed by a speech, with a gameplay sequence in between: we find ourselves swimming from the crashed plane to a lighthouse. We then descend in a bathysphere, and as we do, we hear a recording of a man speaking, just before an underwater city is revealed:

“I am Andrew Ryan, and I'm here to ask you a question. Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow?

'No!' says the man in Washington, 'It belongs to the poor.'

'No!' says the man in the Vatican, 'It belongs to God.'

'No!' says the man in Moscow, 'It belongs to everyone.'

I rejected those answers; instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose... Rapture.

A city where the artist would not fear the censor. Where the scientist would not be bound by… pet-ty mor-al-i-ty. Where the great would not be constrained by the small!

And with the sweat of your brow, Rapture can become your city as well.”

Now, as with some other games on this list, Bioshock's initial line is, in some ways, a lie. "Son" implies parents talking to us, which, as you'll discover in the game, must be a kind of fabrication, as the player character was not raised by conventional parents. Yet, the longer you consider the line, especially if you know where the game's plot goes, the more you see A) that "they" and "son" are ambiguous enough that they could indeed refer to the likely sources of this 'wisdom', and B) that, in some ways, it conveys the exact same sentiment as the bathysphere recording we hear right afterwards -- this Ayn Randian, bullshit nonsense that still sounds so imperiously appealing as a form of fiction for its sheer "fuck you" eloquence and ambition. And what is a game, especially a traditional first-person shooter, if not a promise to the player: you're special, and you're going to do great things…

PORTAL 2

The following from Portal 2 is a tutorial sequence. When we are asked to look up, look down, etc., the game continues with its unseen voice speaking to affirm that we obeyed the command properly. Despite how practical this initially seems, we're about to go full-circle, back to comedy, with an incredibly fun gameplay-based joke. All of this doesn't only set up 'where we are' and 'who we are'; it also establishes a pattern based on controls that will be expected by most players. Even if they're not familiar with such controls, the idea of question → answer in gameplay → affirmation is steadily established.

"Good morning. You have been in suspension for [time] days. In compliance with state and federal regulations, all testing candidates in the Aperture Science Extended Relaxation Center must be revived periodically for a mandatory physical and mental wellness exercise.

"You will hear a buzzer. When you hear the buzzer, look up at the ceiling

"Good. You will hear a buzzer. When you hear the buzzer, look down at the floor

"Good. This completes the gymnastic portion of your mandatory physical and mental wellness exercise.

"There is a framed painting on the wall. Please go stand in frontof it.

"This is art. You will hear a buzzer. When you hear the buzzer, stare at the art.

"You should now feel mentally reinvigorated. If you suspect staring at art has not provided the required intellectual sustenance, reflect briefly on this classical music

[Classical music plays briefly.]

At this point, the game has already started hinting at a joke with a slight intensification: the pattern, which was very physical, has now become mental. The game cannot possibly know if we did indeed reflect on the music, or if we were mentally reinvigorated by the art. Furthermore, there was nothing really being 'tested' in our ability to follow gameplay controls through these steps. Consequently, the game itself, in what it's asking us to do, begins to echo the pointlessness of the in-world experiments of this organisation.

"Good. Now, please return to your bed.”

(After returning to cryostasis, we are awoken by Wheatley, a robotic sphere):

"Hello? Anyone in there? Hello? Are you going to open the door? At any time? Hello? No? Ah! God, you look... um, good. Looking good, actually. Are you okay? Are you--don't answer that. I'm absolutely sure you're fine. There's plenty of time for you to recover. Just take it slow."

Wheatley rescues us, continuing the tutorial and getting us out of there, before checking on our welfare just as the opening moment of the game did, but with some new questions that seem a lot more human and personable:

“Most test subjects do experience some cognitive deterioration after a few months in suspension. Now, you've been under for quite a bit longer, and it's not out of the question that you might have a very minor case of serious brain damage.

But don't be alarmed, alright? Although if you do--if you do feel alarmed, try to hold on to that feeling, because that is the proper reaction to being told you have brain damage.

Do you understand what I'm saying? At all? Does any of this make any sense? Just tell me. Just say 'yes'“

The player is then given a prompt to press a button to 'SPEAK'.

When they press this, the player jumps instead.

"Okay. What you're doing there is jumping. You just... you just jumped.”

The button we were asked to press is, of course, the same button usually used on the PC or console for jumping -- space, X, or A -- and one which muscle-memory in many players will associate with this action.

This joke emerges from the way games often tutorialise things, explaining controls and mechanics to players as they go, frequently in a way that pretends to be narrative in nature. The flimsy link between what we're being asked to do and the game's supposed narrative becomes clearer and more absurd as the sequence progresses, with the game implying more ethereal, mental, and emotional consequences and tests. This narrative framing seems to recede for a moment, only to come thundering back in the punchline: we appear to finally be able to actually 'speak' as a previously silent protagonist, only for this, too, to be yet another gameplay tutorial in disguise, teaching us how to jump.

And in this process, the absurdist, Kafka-esque, pointless, and silly experiments of the Aperture Science laboratory, along with the manipulations of its robots, are all communicated clearly, beat by beat. This includes the potential for emotional and social judgement by these robots. That's essentially what the game and its story are about -- and here, in this opening, we're inducted into the whole thing.

DEATHLOOP

Who are you? —> Who am I? My name? MY NAME? Sonofa - FK! WHAT THE FK’S MY NAME?

Even confusing the base reality in an opening can be a way of setting it up. This is because the most important thing is to put the player in the shoes of the person we're going to be embodying, both narratively and tonally.

The core experience of Deathloop is essentially: an amnesiac brings down the government and militia of a city where everything resets every day. The amnesia is narratively important, not just as a conceit to create a 1:1 match between our own knowledge of the setting and that of our avatar, but because it leads to reveals about our own role and complicity in creating the very status quo we are now trying to defeat. The person asking us "who we are" will have the most direct relationship possible with us in the game -- she is not just our most frequent radio contact, but also an antagonist who relentlessly hunts us down, and even a character we can control in multiplayer to invade other players' single-player games if we wish. Furthermore, the tone of these opening lines themselves perfectly encapsulates this whole dynamic: the panic and humour in not remembering, shortly met by contempt from our strange, soon-to-be antagonist, is indicative of the tone of this entire absurdist comedy.

DISCO ELYSIUM

“REPTILIAN BRAIN - There is nothing.

Only warm, primordial blackness. Your conscience ferments in it - no larger than a single grain of malt. You don't have to do anything any more.”

Another 'amnesiac' investigation game, Disco Elysium, surprisingly doesn't immediately communicate the humorous tone that will follow. However, very soon, through our dialogue choices with our own internal set of 'brain-voices', we gain the option to engage in absurdity. This initial sombreness is fitting because Disco Elysium's use of comedy is in the tradition of works like In Bruges and Bojack Horseman: it's all you can do to laugh, because without laughter, nihilism would melt everything else away. This reflects the truth of how our character feels at the start of this game; laughter becomes an attempt by the soul to reassert itself. So yes, the opening speaks of 'nothing', 'primordial' blackness, and a conscience 'fermenting'. The reference to malt appropriately evokes alcohol, and the notion of abrogated responsibility -- "you don't have to do anything any more" -- is surprisingly reminiscent of the opening of The Stanley Parable.

This opening is directly comparable to Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus and its philosophical exploration of a fundamental, provocative question of human existence: the idea that, all the time, we are not just living; we are choosing not to die. In Disco Elysium, the game commences not with an attempt at literal suicide, but, in some ways worse, with soul-suicide and ego-death -- an attempt to blot out our brain and personality. The tone of this opening communicates the kind of story we're about to engage in by showing us this existential state.

DOOM 2016

And finally, we have one of the funniest and best establishings of a core experience in video game history: the 2016 DOOM. After an era of adding 'prestige drama' into reboots of classic franchises, this game begins with the player's POV character curling their hand into a fist and effectively punching the very idea of narrative elevation in the face. The message is clear: we're angry, there's a bunch of fucked-up demons, we're in space, and we don't want a storyline, thank you very much. Which is - of course - a story! Comedy!

Punch!